in what way is the composer josquin related to palestrina and the catholic church?

A 1611 woodcut of Josquin des Prez, copied from a now-lost oil painting executed during his lifetime.[i]

Josquin des Prez (French: [ʒɔskɛ̃ depʁe]; c. 1450–1455 – 27 Baronial 1521; built-in Josquin Lebloitte) was a French composer of high Renaissance music.[2] The central effigy of the Franco-Flemish School, Josquin is widely considered the beginning principal of the circuitous Renaissance mode of polyphony which emerged during his lifetime. His career spanned French republic and Italia under the patronage of the House of Sforza, two popes, Louis XII and Ercole I d'Este amidst others, yet the details of his activity are shadowy, and virtually cypher is known virtually his personality. More than 370 works are attributed to him;[iii] information technology was only after the advent of modern analytical scholarship that some of these attributions were challenged and revealed equally mistaken, on the basis of stylistic features and manuscript evidence. Regardless, he was among the most innovative and well-known composers of his time, exerting a profound influence on both his contemporaries and subsequent composers.

Josquin wrote both sacred and secular music, and in all of the meaning vocal forms of the fourth dimension, including masses, motets, chansons and frottole. During the 16th century, he was praised for his melodic gift and his utilise of technical devices. In modern times, scholars have attempted to ascertain the basic details of his biography, and have tried to define the key characteristics of his way to correct misattributions. This has proven difficult, as Josquin sometimes wrote in an ascetic style devoid of ornamentation, and at other times he produced music requiring considerable virtuosity.[4] Heinrich Glarean wrote in 1547 that Josquin was not only a "magnificent virtuoso" (the original Latin may be translated besides every bit "bear witness-off") simply capable of being a "mocker", using satire effectively.[v] While the focus of scholarship in recent years has been to remove music from the "Josquin catechism" (including some of his most famous pieces) and to reattribute it to his contemporaries, the remaining music represents some of the most famous and enduring of the Renaissance.[vi]

Proper noun [edit]

Josquin'southward full proper name is 'Jossequin Lebloitte dit Desprez', a fact unknown to scholars until the late 20th century.[7] This information stems from a pair of documents found in Condé dated to 1483, where he is referred to as the nephew of Gille Lebloitte dit Desprez and the son of Gossard Lebloitte dit Desprez.[viii] The discussion "dit" is used to point mutual police force names, and documents about Josquin'southward begetter and grandfather seems to indicate that the surname Desprez (or "despres"/"des pres") have been used in the family unit for at least two generations, maybe to distinguish them from other branches of the Lebloitte family unit.[9] The name "Lebloitte" is extremely rare and the reason that Josquin'due south family took upward the more mutual surname "Desprez" remains uncertain.[10]

The proper noun "Josquin" is a atomic form of Josse, the French form of the name of a Judoc, a Breton saint of the seventh century.[11] During the 15th and 16th centuries, the proper noun Josquin was common in regions of Flanders and Northern France.[2] This later name is given under a broad variety of spellings in French, Italian, and Latin, including 'Iosquinus Pratensis' and 'Iodocus a Prato'. His motet Illibata Dei virgo nutrix includes an acrostic of his name, where he spelled it "IOSQVIN Des PREZ".[12] Afterward documents from Condé, where he lived for the last years of his life, always referred to him as "Maistre Josse Desprez". This includes a letter of the alphabet written by the chapter of Notre-Dame de Condé to Margaret of Republic of austria where he is named equally "Josquin Desprez".[13] Opinions on whether his surname should exist written as 1 discussion ("Desprez") or two ("des Prez") are divided, with publications in English language preferring the latter and publications from continental Europe preferring the former.[14]

Life [edit]

Birth and background [edit]

Hainault and the surrounding area in the time of Josquin

Josquin's father and grandfather were both called, amid other forms, Gossard des Pres. Both of them likewise served successively equally sergent or policeman in the castellany of Ath, a subdivision of the County of Hainaut, and they were active in the region between Tournai and Ath. The elder Gossard was documented from 1393 to 1425, and afterward became the mayor of Saint-Sauveur, a village in which Josquin later held a benefice. The younger Gossard commenced his duty as policeman no afterwards than 1440, and disappeared from the records in 1448 after a less than distinguished career.[fifteen] Around 1466, perhaps on the death of his father, Josquin was named by his uncle and aunt, Gille Lebloitte dit Desprez and Jacque Banestonne, as their heir. Their will gives Josquin'south surname equally Lebloitte. According to Matthews and Merkley, "des Prez" was an alternative name.[xvi] The younger Gossard, Josquin'southward father, has definitely died by the time Josquin took up his inheritance in 1483 since the documents describe him equally deceased.

There is trivial known for certain near Josquin's early on life.[17] Much is inferential and speculative, and has been the subject of immense discussion between scholars for centuries; the musicologist William Elders noted that "it could be called a twist of fate that neither the year, nor the place of nativity of the greatest composer of the Renaissance is known".[vii] Josquin is traditionally held to have been born c. 1450. A now-outdated theory held that he was born in around 1440, as he was long mistaken for another man, Jushinus de Kessalia, whose proper noun was recorded in some documents as "Judocus de Picardia".[14] [due north 1] A reevaluation of his later on career trajectory, name and family background has made this merits impossible.[17] Modern scholarship now continues to favor a birthdate around 1450, and at the latest 1455.[17] This would make him nearly the same age as his contemporaries, Loyset Compère and Heinrich Isaac, and slightly older than Jacob Obrecht.[17]

Josquin was born somewhere in the French-speaking area of Flanders, modern-day northeastern France or Belgium.[18] Despite his shut clan with Condé-sur-l'Escaut later in his life, mod scholarship has ended that this was not his birthplace.[17] [14] [northward two] The only solid evidence for his verbal birthplace is a later on legal document in which Josquin himself described being built-in from beyond Noir Eauwe,[17] literally the "Black Water".[14] The exact pregnant of this has puzzled scholars, and a variety of theories have been adult on which body of h2o is being referred to.[17] The L'Eau Noire river in the Ardennes has been proposed, and there is known to have been a hamlet named 'Prez' in that location,[17] though Fallows contends that the complications surrounding Josquin's proper noun makes a surname connection irrelevant, and that the river is too small and far from Condé to be a candidate.[19] Instead, Fallows proposes a birthplace near the rivers which meet at Condé, the Escaut and Haine, preferring the latter since it was known for transporting coal, which might have made the river fit the "Blackness Water" description.[20] If the Haine theory is correct, that would mean Josquin was born in the County of Hainaut, which would fit with a 1560 poetry by the poet Pierre de Ronsard which labels Josquin as such.[21] Other theories include a birth near Saint-Quentin, Aisne, due to his early clan with the Collegiate Church of Saint-Quentin, or in the small village of Beaurevoir, which is near Escaut, a river that may be referred to by an acrostic in his subsequently motet Illibata Dei virgo nutrix.[17] [n iii]

Early on life [edit]

No sure documents surviving apropos Josquin's education or upbringing.[22] Fallows identifies him with 'Goseequin de Condent', recorded equally an chantry male child at the collegiate church of Saint-Géry, Cambrai until the summer of 1466.[23] Other scholars such as Gustave Reese relay a 17th-century account of from Cardinal Richelieu's friend Claude Hémeré, who contended that Josquin became a choirboy with his friend Jean Mouton at the Collegiate Church of Saint-Quentin,[22] though doubt has been bandage of the reliabillity of this account.[17] Josquin may have studied counterpoint under Ockeghem, whom he greatly admired throughout his life: this is suggested both by the testimony of Gioseffo Zarlino and Lodovico Zacconi, writing after in the 16th century, and past Josquin's lamentation on the decease of Ockeghem in 1497, Nymphes des bois/Requiem aeternam.[17] All records from Saint-Quentin were destroyed in 1669; all the same, the collegiate chapel there was a center of musicmaking for the entire surface area, and was an important centre of purple patronage. Jean Mouton and Loyset Compère were buried there and it is possible that Josquin acquired his later connections with the French imperial chapel through early experiences at Saint-Quentin.[17]

The first definite tape of Josquin'south employment is dated 19 April 1477, and shows that he was a vocalizer at the chapel of René, Duke of Anjou, in Aix-en-Provence. He remained in that location at least until 1478. No certain records of his movements exist for the catamenia from March 1478 to 1483, but if he remained in the employ of René he would take transferred to Paris in 1481 along with the residual of the chapel. One of Josquin's early motets, Misericordias Domini in aeternum cantabo, suggests a direct connection with Louis Xi, who was male monarch during this time. In 1483, Josquin returned to Condé to claim his inheritance from his aunt and uncle, who may have been killed by the ground forces of Louis Eleven in May 1478, when they besieged the town, locked the population into the church, and burned them alive.[24]

The period from 1480 to 1482 has puzzled biographers; contradictory evidence exists suggesting either that Josquin was still in France, or that he was already in the service of the Sforza family unit, specifically with Ascanio Sforza, who had been banished from Milan and resided temporarily in Ferrara or Naples. Residence in Ferrara in the early 1480s could explicate the Missa Hercules dux Ferrariae, composed for Ercole d'Este, but which stylistically does not fit with the usual date of 1503–04 when Josquin was known to be in Ferrara. Alternatively it has been suggested that Josquin spent some of that fourth dimension in Republic of hungary, based on a mid-16th-century Roman document describing the Hungarian courtroom in those years, and including Josquin equally i of the musicians present.[25]

Milan and travels: Sforza employment [edit]

| Date | Location | Confidence |

|---|---|---|

| March 1483 | Condé | Certainly |

| August 1483 | Deviation from Paris | Possibly |

| March 1484 | Rome | Possibly |

| June–August 1484 | Milan (with Ascanio) | Certainly |

| Upwardly to July 1484 | Rome (with Ascanio) | Certainly |

| July 1485 | Plans to leave (with Ascanio) | Certainly |

| 1485 – ? | Hungary | Peradventure |

| January – Feb 1489 | Milan | Certainly |

| Early May 1489 | Milan | Probably |

| June 1489 | Rome (in Sistine Chapel Choir) | Certainly |

Though he may arrived immediately after his 1483 trip to Condé, a surviving record indicates that Josquin was in Milan past at to the lowest degree 15 May 1484.[25] By this fourth dimension, Milan had become the musical center of Europe, with sacred music of the Milan Cathedral in particular having a reputation for excellence.[27] It was common for composers to galvanize their careers in Italy, as forth with Milan, the courts in Naples and Ferrara were emerging as musically prominent, while the musical establishment of Josquin's native Burgundy had been declining since the expiry of Charles the Assuming in 1477.[28] Josquin was employed by the Firm of Sforza, with a surviving record from twenty June 1984 stating his employment in service of the fundamental Ascanio Sforza.[29]

While in their employ, he made one or more trips to Rome, and mayhap also to Paris; while in Milan he fabricated the acquaintance of Franchinus Gaffurius, who was maestro di cappella of the cathedral there. He was in Milan again in 1489, afterwards a possible period of travel; but he left that year.[thirty]

Rome [edit]

From 1489 to 1495, Josquin was a fellow member of the papal choir, first nether Pope Innocent VIII, and later nether the Borgia pope Alexander Half dozen. He may take gone there as role of a vocaliser exchange with Gaspar van Weerbeke, who went dorsum to Milan at the same time. While there, he may have been the one who carved his name into the wall of the Sistine Chapel; a "JOSQUINJ" was revealed by workers restoring the chapel in 1998. Since it was traditional for singers to carve their names into the walls, and hundreds of names were inscribed in that location during the period from the 15th to the 18th centuries, information technology is considered highly likely that the graffiti is past Josquin—and if then, it would exist his only surviving autograph.[31] [32] [33]

Josquin'southward mature mode evolved during this period; equally in Milan he had absorbed the influence of light Italian secular music, in Rome he refined his techniques of sacred music. Several of his motets have been dated to the years he spent at the papal chapel.

Difference from Rome; Milan and French republic [edit]

Effectually 1498, Josquin nigh likely re-entered the service of the Sforza family, on the evidence of a pair of messages between the Gonzaga and Sforza families.[34] He probably did not stay in Milan long, for in 1499 Louis XII captured Milan in his invasion of northern Italy and imprisoned Josquin'due south former employers. Around this time Josquin most likely returned to French republic, although documented details of his career around the plow of the 16th century are lacking. Prior to parting Italy, he almost likely wrote one of his most famous secular compositions, the frottola El Grillo, too as In te Domine speravi ("I accept placed my hope in you, Lord"), based on Psalm 30. The latter limerick may have been a veiled reference to the religious reformer Girolamo Savonarola, who had been burned at the stake in Florence in 1498, and for whom Josquin seems to have had a special reverence; the text was the Dominican friar'southward favorite psalm, a meditation on which he left incomplete in prison prior to his execution.[35]

Some of Josquin'due south compositions, such as the instrumental Vive le roy, have been tentatively dated to the flow effectually 1500 when he was in France. A motet, Memor esto verbi tui servo tuo ("Call back thy promise unto thy servant"), was, according to Heinrich Glarean writing in the Dodecachordon of 1547, composed as a gentle reminder to the king to proceed his promise of a benefice to Josquin, which he had forgotten to keep. According to Glarean's story, information technology worked: the courtroom applauded, and the rex gave Josquin his benefice. Upon receiving information technology, Josquin reportedly wrote a motet on the text Benefecisti servo tuo, Domine ("Lord, thou hast dealt graciously with thy retainer") to show his gratitude to the king.[36]

Ferrara [edit]

Ercole I d'Este was an of import patron of the arts during the Italian Renaissance; he was Josquin'due south employer in 1503 and 1504.

Josquin probably remained in the service of Louis XII until 1503, when Duke Ercole I of Ferrara hired him for the chapel there.[37] I of the rare mentions of Josquin's personality survives from this time. Prior to hiring Josquin, one of Duke Ercole's administration recommended that he hire Heinrich Isaac instead, since Isaac was easier to get along with, more companionable, was more than willing to compose on demand, and would toll significantly less (120 ducats vs. 200). Ercole, however, chose Josquin.[38]

While in Ferrara, Josquin wrote some of his nigh famous compositions, including the austere, Savonarola-influenced Miserere,[39] which became one of the most widely distributed motets of the 16th century; the utterly contrasting, virtuoso motet Virgo salutiferi;[40] and possibly the Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae, which is written on a cantus firmus derived from the musical letters in the Duke'south proper name, a technique known as soggetto cavato.

Josquin did not stay in Ferrara long. An outbreak of the plague in the summer of 1503 prompted the evacuation of the Duke and his family, as well as two-thirds of the citizens, and Josquin left by Apr of the next year, possibly also to escape the plague. His replacement, Jacob Obrecht, died of the plague in the summertime of 1505,[38] to exist replaced past Antoine Brumel in 1506, who stayed until the disbanding of the chapel in 1510.

Retirement to Condé-sur-l'Escaut [edit]

Josquin went straight from Ferrara to his home region of Condé-sur-l'Escaut, southeast of Lille on the nowadays-twenty-four hours border between Belgium and France, becoming provost of the collegiate church of Notre-Dame on three May 1504, a large musical establishment that he headed for the residue of his life.[41] While the chapter at Bourges Cathedral asked him to become master of the choirboys there in 1508, it is non known how he responded, and there is no record of his having been employed there; most scholars presume he remained in Condé.[42] In 1509, he held concurrently provost and choir master offices at Saint Quentin collegiate church.

During the last two decades of his life, Josquin's fame spread away along with his music. The newly developed engineering science of press made wide dissemination of his music possible, and Josquin was the favorite of the first printers: i of Petrucci's first publications, and the earliest surviving impress of music by a single composer, was a book of Josquin's masses which he printed in Venice in 1502. This publication was successful enough that Petrucci published ii further volumes of Josquin's masses, in 1504 and 1514, and reissued them several times.[43]

On his death-bed, Josquin asked that he be listed on the rolls as a foreigner, so that his property would not laissez passer to the Lords and Ladies of Condé.[41] This bit of evidence has been used to show that he was French by birth. Additionally, he left an endowment for the performance of his belatedly motet, Pater noster, at all general processions in the boondocks when they passed in front of his house, stopping to place a wafer on the marketplace altar to the Holy Virgin. Pater noster may have been his last piece of work.[44]

Music [edit]

Overview [edit]

Josquin lived during a transitional stage in music history. Musical styles were irresolute rapidly, in part attributable to the movement of musicians between unlike regions of Europe.[45] Many northern musicians moved to Italian republic, the eye of the Renaissance, attracted past the Italian nobility's patronage of the arts; while in Italia, these composers were influenced by the native Italian styles, and often brought those ideas with them back to their homelands. The sinuous musical lines of the Ockeghem generation, the contrapuntal complexity of the Netherlanders, and the homophonic textures of the Italian lauda and secular music began to merge into a unified fashion; indeed Josquin was to be the leading figure in this musical process, which eventually resulted in the formation of an international musical language, of which the most famous composers included Palestrina and Lassus.[46]

Josquin probable learned his craft in his home region in the Due north, in French republic, and then in Italy when he went to Milan and Rome. His early on sacred works emulate the contrapuntal complexity and ornamented, melismatic lines of Ockeghem and his contemporaries, but at the same time he was learning his contrapuntal technique he was acquiring an Italianate idiom for his secular music: subsequently all, he was surrounded past Italian pop music in Milan. By the terminate of his long creative career, which spanned approximately l productive years, he had developed a simplified style in which each vocalisation of a polyphonic limerick exhibited gratis and shine move, and close attention was paid to clear setting of text equally well every bit clear alignment of text with musical motifs. While other composers were influential on the development of Josquin's fashion, especially in the late 15th century, he himself became the most influential composer in Europe, especially subsequently the development of music printing, which was concurrent with the years of his maturity and peak output. This result made his influence fifty-fifty more decisive than it might otherwise have been.

Many "modern" musical compositional practices were being born in the era around 1500. Josquin made extensive apply of "motivic cells" in his compositions, short, easily recognizable melodic fragments which passed from voice to voice in a contrapuntal texture, giving it an inner unity. This is a bones organizational principle in music which has been practiced continuously from approximately 1500 until the present day.[47]

Josquin wrote in all of the important forms current at the time, including masses, motets, chansons, and frottole. He even contributed to the development of a new course, the motet-chanson, of which he left at least three examples. In addition, some of his pieces were probably intended for instrumental functioning.

Each area of his output can be further subdivided by form or by hypothetical period of composition. Since dating Josquin's compositions is particularly problematic, with scholarly consensus only achieved on a minority of works, discussion here is by type.

Masses [edit]

Manuscript showing the opening Kyrie of the Missa de Beata Virgine, a tardily work. Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Capp. Sist. 45, ff. 1v-2r.

Josquin wrote towards the end of the period in which the mass was the predominant grade of sacred composition in Europe. The mass, as information technology had developed through the 15th century, was a long, multi-department form, with opportunities for large-scale construction and system not possible in the other forms such as the motet. Josquin wrote some of the most famous examples of the genre, most using some kind of cyclic organization.

He wrote masses using the post-obit general techniques, although there is considerable overlap betwixt techniques in individual compositions:

- cantus firmus mass, in which a pre-existing tune appeared, mostly unchanged, in ane vocalisation of the texture, with the other voices being more than or less freely equanimous;

- paraphrase mass, in which a pre-existing tune was used freely in all voices, and in many variations;

- parody mass, in which a pre-existing multi-vocalism song appeared in whole or in part, with textile from all voices in use, not just the tune;

- soggetto cavato, or solmization mass, in which the melody is drawn from the syllables of a proper noun or phrase (for example "la sol fa re mi"—A, 1000, F, D, E—based on the syllables of Lascia fare mi ("allow me do it", a phrase used by an unknown patron, in a context around which much legend has arisen).

- catechism, in which an unabridged mass is based on canonic techniques, and no pre-existing material has been identified.[48]

Well-nigh of these techniques, particularly paraphrase and parody, became standardized during the first half of the 16th century; Josquin was very much a pioneer, and what was perceived by later observers as the mixing of these techniques was actually the procedure by which they were created.[46]

Cantus-firmus masses [edit]

Prior to Josquin'southward mature catamenia, the most common technique for writing masses was the cantus firmus, a technique which had been in use already for most of the 15th century. Information technology was the technique that Josquin used earliest in his career, with the Missa L'ami Baudichon, possibly his first mass.[46] This mass is based on a secular—indeed ribald—tune similar to "Iii Blind Mice". That basing a mass on such a source was an accepted procedure is evident from the being of the mass in Sistine Chapel part-books copied during the papacy of Julius Two (1503 to 1513).[49]

Josquin'due south most famous cantus-firmus masses are the 2 based on the Fifty'homme armé tune, which was the favorite tune for mass composition of the unabridged Renaissance. The before of the two, Missa Fifty'homme armé super voces musicales, is a technical bout-de-strength on the tune, containing numerous mensuration canons and contrapuntal display. It was by far the well-nigh famous of all his masses.[50] The second, Missa L'homme armé sexti toni, is a "fantasia on the theme of the armed man."[51] While based on a cantus firmus, it is too a paraphrase mass, for fragments of the tune announced in all voices. Technically information technology is about restrained, compared to the other L'homme armé mass, until the closing Agnus Dei, which contains a complex canonic structure including a rare retrograde catechism, around which other voices are woven.[52]

Paraphrase masses [edit]

The paraphrase technique differs from the cantus-firmus technique in that the source cloth, though it nevertheless consists of a monophonic original, is embellished, oftentimes with ornaments. As in the cantus-firmus technique, the source melody may appear in many voices of the mass.

Several of Josquin's masses feature the paraphrase technique, and they include some of his virtually famous work including the great Missa Gaudeamus. The relatively early Missa Ave maris stella, which probably dates from his years in the Sistine Chapel choir, paraphrases the Marian antiphon of the same name; it is likewise one of his shortest masses.[53] The late Missa de Beata Virgine paraphrases plainchants in praise of the Virgin Mary; it is a Lady Mass, a votive mass for Saturday performance, and was his most pop mass in the 16th century.[46] [54]

Past far the well-nigh famous of Josquin's masses using the technique, and ane of the almost famous mass settings of the entire era, was the Missa pange lingua, based on the hymn past Thomas Aquinas for the Vespers of Corpus Christi. It was probably the last mass that Josquin composed.[55] This mass is an extended fantasia on the tune, using the melody in all voices and in all parts of the mass, in elaborate and ever-irresolute polyphony. 1 of the high points of the mass is the et incarnatus est section of the Credo, where the texture becomes homophonic, and the tune appears in the topmost voice; here the portion which would ordinarily set "Sing, O my tongue, of the mystery of the divine torso" is instead given the words "And he became incarnate by the Holy Ghost from the Virgin Mary, and was made man."[56]

Parody masses, masses on pop songs [edit]

In parody masses, the source material was not a single line, merely an entire texture, often of a popular song. Several works by Josquin fall loosely into this category, including the Missa Fortuna desperata, based on the three-voice song Fortuna desperata (possibly by Antoine Busnois); the Missa Malheur me bat (based on a chanson variously ascribed to Obrecht, Ockeghem, or, most likely, Abertijne Malcourt);[46] and the Missa Mater Patris, based on a three-phonation motet by Antoine Brumel. The Missa Mater Patris is probably the outset true parody mass to be equanimous, for it no longer contains any hint of a cantus firmus.[57] Parody technique was to get the most usual ways of mass composition for the remainder of the 16th century, although the mass gradually fell out of favor as the motet grew in esteem.

Masses on solmization syllables [edit]

The primeval known mass past any composer using this method of composition—the soggetto cavato—is the Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae, which Josquin probably wrote in the early on 1480s for the powerful Ercole I, Duke of Ferrara. The notes of the cantus firmus are drawn from the musical syllables of the Knuckles's name in the following way: Ercole, Duke of Ferrara in Latin is Hercu50edue south Du10 Feastwardrrarie . Taking the solmization syllables with the same vowels gives: Re–Ut–Re–Ut–Re–Fa–Mi–Re [58] (in modern nomenclature: D–C–D–C–D–F–E–D). Another mass using this technique is the Missa La sol fa re mi, based on the musical syllables independent in "Lascia fare mi" ("permit me exercise it"). The story, as told past Glareanus in 1547, was that an unknown aristocrat used to guild suitors abroad with this phrase, and Josquin immediately wrote an "exceedingly elegant" mass on it as a jab at him.[59]

Canonic masses [edit]

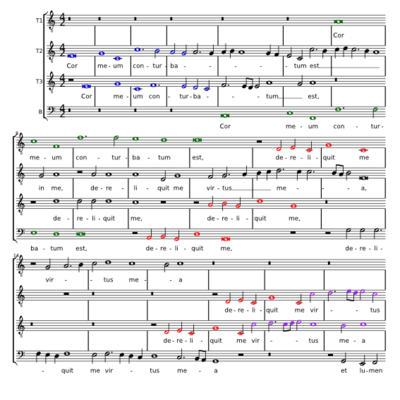

Opening of the Agnus Dei II from the Missa L'homme armé super voces musicales. ![]() Play(help·info) The movement consists of a iii-out-of-one mensuration canon. The middle vox is the slowest; the lowest vocalism sings at twice the speed of the middle voice, and the height voice at three times the speed. The first four notes of the canon are shown continued by lines of the same color. (The offset viii notes of the canon are a quotation of the contratenor of Ockeghem's "Ma bouche rit".)

Play(help·info) The movement consists of a iii-out-of-one mensuration canon. The middle vox is the slowest; the lowest vocalism sings at twice the speed of the middle voice, and the height voice at three times the speed. The first four notes of the canon are shown continued by lines of the same color. (The offset viii notes of the canon are a quotation of the contratenor of Ockeghem's "Ma bouche rit".)

Canonic masses came into increasing prominence in the latter part of the 15th century. Early examples include Ockeghem'southward famous Missa prolationum, consisting entirely of mensuration canons, the Missa L'homme armé of Guillaume Faugues, whose cantus firmus is presented in canon at the descending 5th, the Missa [Ad fugam] of Marbrianus de Orto, based on freely composed canons at the fifth between superius and tenor, and the two nifty canonic masses of Josquin, the Missa Advertizing fugam and Missa Sine nomine. Josquin makes use of canon in the Osanna and Agnus Dei III of the Missa L'homme armé sexti toni, throughout the Missa Sine nomine and Missa Advertizement fugam, and in the terminal iii movements of the Missa De beata virgine. The Missa Fifty'homme armé super voces musicales incorporates mensuration canons in the Kyrie, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei Two.[threescore]

Motets [edit]

Josquin'southward motet fashion varied from almost strictly homophonic settings with block chords and syllabic text declamation to highly ornate contrapuntal fantasias, to the psalm settings which combined these extremes with the add-on of rhetorical figures and text-painting that foreshadowed the afterward development of the madrigal. He wrote many of his motets for four voices, an ensemble size which had become the compositional norm effectually 1500, and he was also a considerable innovator in writing motets for 5 and six voices.[61] No motets of more than six voices take been reliably attributed to Josquin.

Well-nigh all of Josquin's motets use some kind of compositional constraint on the procedure; they are not freely composed.[62] Some of them utilise a cantus firmus as a unifying device; some are canonic; some use a motto which repeats throughout; some utilize several of these methods. The motets that use canon can be roughly divided into two groups: those in which the canon is plainly designed to be heard and appreciated as such, and another group in which a catechism is present, but most impossible to hear, and seemingly written to be appreciated by the eye, and by connoisseurs.[63]

Josquin often used false, especially paired imitation, in writing his motets, with sections akin to fugal expositions occurring on successive lines of the text he was setting. An example is his setting of Dominus regnavit (Psalm 93), for four voices; each of the lines of the psalm begins with a vocalism singing a new tune alone, rapidly followed by entries of other 3 voices in imitation.[64]

In writing polyphonic settings of psalms, Josquin was a pioneer, and psalm settings form a large proportion of the motets of his later on years. Few composers prior to Josquin had written polyphonic psalm settings.[65] Some of Josquin's settings include the famous Miserere, written in Ferrara in 1503 or 1504 and most probable inspired by the recent execution of the reformist monk Girolamo Savonarola,[66] Memor esto verbi tui, based on Psalm 119, and two settings of De profundis (Psalm 130), both of which are often considered to be amidst his most significant accomplishments.[64] [67]

Chansons and instrumental compositions [edit]

In the domain of secular music, Josquin left numerous French chansons, for from three to six voices, as well as a handful of Italian secular songs known every bit frottole, too as some pieces which were probably intended for instrumental performance. Issues of attribution are even more acute with the chansons than they are with other portions of his output: while about 70 3 and four-voice chansons were published under his name during his lifetime, only half dozen of the more than thirty five- and six-vox chansons attributed to him were circulated under his name during the same time. Many of the attributions added after his death are considered to be unreliable, and much work has been washed in the final decades of the 20th century to correct attributions on stylistic grounds.[68]

Josquin's earliest chansons were probably composed in northern Europe, nether the influence of composers such as Ockeghem and Busnois. Unlike them, however, he never adhered strictly to the conventions of the formes fixes—the rigid and complex repetition patterns of the rondeau, virelai, and ballade—instead he often wrote his early on chansons in strict imitation, a characteristic they shared with many of his sacred works.[46] He was one of the first composers of chansons to brand all voices equal parts of the texture; and many of his chansons comprise points of false, in the manner of motets. However he did use melodic repetition, especially where the lines of text rhymed, and many of his chansons had a lighter texture, too as a faster tempo, than his motets.

Inside of his chansons, he often used a cantus firmus, sometimes a popular vocal whose origin tin no longer be traced, as in Si j'avoye Marion.[69] Other times he used a tune originally associated with a separate text; and still other times he freely equanimous an entire song, using no credible external source material. Another technique he sometimes used was to have a popular song and write it as a catechism with itself, in two inner voices, and write new melodic material to a higher place and effectually it, to a new text: he used this technique in 1 of his most famous chansons, Faulte d'silvery ("The problem with money"), a song sung past a man who wakes in bed with a prostitute, broke and unable to pay her.

Some of his chansons were doubtless designed to exist performed instrumentally. That Petrucci published many of them without text is stiff evidence of this; additionally, some of the pieces (for example, the fanfare-like Vive le roy) contain writing more idiomatic for instruments than voices.[46]

Josquin's most famous chansons circulated widely in Europe. Some of the better known include his complaining on the death of Ockeghem, Nymphes des bois/Requiem aeternam; Mille regretz (the attribution of which has recently been questioned);[70] Plus nulz regretz; and Je me complains.

In add-on to his French chansons, Josquin wrote at least iii pieces in the manner of the Italian frottola, a pop Italian vocal form which he would accept encountered during his years in Milan. These songs include Scaramella, El grillo, and In te domine speravi. They are even simpler in texture than his French chansons, being nigh uniformly syllabic and homophonic, and they remain among his most frequently performed pieces.

Motet-chansons [edit]

While in Milan, Josquin wrote several examples of a new blazon of piece developed past the composers at that place, the motet-chanson. These compositions were texturally very like to 15th century chansons in the formes fixes mold, except that unlike those completely secular works, they contained a dirge-derived Latin cantus-firmus in the lowest of the three voices. The other voices, in French, sang a secular text which had either a symbolic relationship to the sacred Latin text, or commented on it.[71] Josquin'south three known motet-chansons, Que vous madame/In pace, A la mort/Monstra te esse matrem, and Fortune destrange plummaige/Pauper sum ego, are like stylistically to those by the other composers of the Milan chapel, such as Loyset Compère and Alexander Agricola.

Influence and reputation [edit]

During the 16th century, Josquin acquired the reputation of the greatest composer of the age, his mastery of technique and expression universally imitated and admired. Writers equally diverse as Baldassare Castiglione and Martin Luther wrote about his reputation and fame, with Luther declaring that "he is the master of the notes. They must practice as he wills; equally for the other composers, they have to practise as the notes volition."[73] Theorists such equally Heinrich Glarean and Gioseffo Zarlino held his style as that all-time representing perfection.[74] Josquin'southward fame was just eclipsed after the beginning of the Baroque era, with the decline of the pre-tonal polyphonic style. During the 18th and 19th centuries Josquin'southward fame was overshadowed by later Roman Schoolhouse composer Palestrina, whose music was seen as the peak of polyphonic refinement, and codified into a system of composition by theorists such equally Johann Fux. Despite the decline of popularity in Josquin's music during this time, Josquin'southward influence in music across the 15th century cannot be overstated. Travelling Franco-Flemish composers like Josquin were a primary component in Italian chapels. They used their unique styles and ideas to influence Italian music, thus contributing to iconic Italian genres such equally the madrigal.[75] During the 20th century, Josquin'south reputation has grown steadily, to the point where scholars over again consider him "the greatest and most successful composer of the age."[76] [77] Due to Josquin's popularity, scholars accept worked diligently to weed out misattributed works. To sell more copies of their compositions, information technology was not uncommon for composers or publishers to put Josquin'due south name on their work both during and after Josquin's lifetime. Assay of dissonance treatments and cantus firmi have helped scholars in the past decades to determine which pieces were nigh likely written by Josquin himself.[78] According to Richard Sherr, writing in the introduction to the Josquin Companion, addressing specifically the shrinking of Josquin's canon due to correction of misattributions, "Josquin will survive because his best music actually is as magnificent as everybody has e'er said it was."[half-dozen]

Since the 1950s Josquin'southward reputation has been boosted past the increasing availability of recordings, of which there are many, and the rise of ensembles specializing in the functioning of 16th century vocal music, many of which place Josquin's output at the heart of their repertoire.[79]

References [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ See Roth 2000 for farther information concerning "Judocus de Picardia".

- ^ The rejection of Condé-sur-l'Escaut near the County of Hainaut as Josquin'due south birthplace is because when Josquin lived in Condé later on in his life he labeled himself an aubain (greenhorn) indicating that he was not native to Condé.[17] [14]

- ^ Reese et al. 1984, p. 2 notes that interpreting this unconventional remains "conjectural", and that numerous scholars have offered unlike interpretations

Citations [edit]

- ^ Macey et al., §8.

- ^ a b Macey et al. 2011.

- ^ Wegman, p. 28.

- ^ Sherr, p. 3.

- ^ Glareanus, quoted in Sherr, p. 3.

- ^ a b Sherr, p. x.

- ^ a b Elders 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Matthews & Merkley 1998, pp. 208–215.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 12.

- ^ Matthews & Merkley 1998, p. 214, footnote.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. ix.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 52.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d east Fallows 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Kellman

- ^ Matthews and Merkley, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j k l m Macey et al. 2011, §1 "Nativity, family and early on training (c1450–75)".

- ^ Sherr 2017, "Introduction".

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 19.

- ^ Fallows 2020, pp. xix–20.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 20.

- ^ a b Reese et al. 1984, p. 3.

- ^ Fallows 2020, pp. 13, 35.

- ^ Macey et al. 2011, §two "Aix-en-Provence, ?Paris, Condé-sur-fifty'Escaut (c1475–1483)".

- ^ a b Macey et al. 2011, §iii "Milan and elsewhere (1484–9)".

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 118.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 109.

- ^ Fallows 2020, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Fallows 2020, p. 110.

- ^ Fallows, David (Apr 1996). "Josquin and Milan". Plainsong and Medieval Music. v (1): 69–80. doi:10.1017/S0961137100001078. ISSN 0961-1371.

- ^ Pietschmann

- ^ Sherr, frontispiece

- ^ Wegman, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Macey et al., §5.

- ^ Macey, p. 155.

- ^ David W. Barber, If It Ain't Baroque: More Music History as It Ought to Be Taught (Toronto: Sound and Vision, 1992), p. 34.

- ^ Merkley, pp. 544–583.

- ^ a b Macey et al., §6.

- ^ Macey, p. 184.

- ^ Milsom, p. 307.

- ^ a b Sherr, p. 16.

- ^ Sherr, p. 17.

- ^ Boorman, Stanley. "Petrucci, Ottaviano (dei)." Music Printing and Publishing. New York: Norton, 1990, pp. 365–369.

- ^ Milsom, pp. 303–305.

- ^ Reese, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c d e f g Noble, Grove (1980)

- ^ Irving Godt, JMT, 264–292.

- ^ Blackburn, Planchart, Bloxham, Sherr, in Sherr, 51–248.

- ^ Blackburn, p. 72.

- ^ Blackburn, pp. 53–62

- ^ Blackburn, p. 63

- ^ Blackburn, p. 64

- ^ Planchart, in Sherr, p. 109.

- ^ Planchart, in Sherr, pp. 120–130

- ^ Planchart, in Sherr, pp. 130, 132.

- ^ Planchart, in Sherr, p. 142.

- ^ Reese, p. 240.

- ^ Taruskin, p. 560.

- ^ Blackburn, p. 78.

- ^ A canon from the Agnus Dei II from the Missa L'homme armé super voces musicales is written in a triangular course in Dosso Dossi's Apologue of Music. Encounter the entry Eye music.

- ^ Milsom, p. 282

- ^ Milsom, p. 284

- ^ Milsom, p. 290

- ^ a b Reese, p. 249

- ^ Reese, p. 246

- ^ Macey, p. xxx

- ^ Milsom, p. 305

- ^ Louise Litterick, in Sherr, pp. 335, 393

- ^ Dark-brown, Grove (1980), "Chanson."

- ^ Litterick, in Sherr, pp. 374–376

- ^ Litterick, in Sherr, p. 336

- ^ "Tableau et cadre: Portrait de Josquin des Près" [Painting and Frame: Portrait of Josquin des Près] (in French). Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Burkholder, J. Peter, Donald Jay Grout, and Claude V. Palisca. A History of Western Music. Ninth edition. New York, N.Y.: Westward. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2014, pp. 203.

- ^ Wegman, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Bowen, William. "The Contribution of French Musicians to the Genesis of the Italian Madrigal". Renaissance & Reformation/Renaissance et Reforme. 27 (ii): 101–14.

- ^ David Fallows, in Sherr, p. 575.

- ^ Higgins.

- ^ Rodin, Jesse (2006). "A Josquin Commutation". Early Music. 34 (2): 249–257. doi:10.1093/em/cal002. JSTOR 3805844. S2CID 191649267.

- ^ Sherr, p. 577; also Appendix B (Discography)

Sources [edit]

- Brown, Howard M. "Chanson" The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. London, Macmillan, 1980. (20 vol.) ISBN i-56159-174-two.

- Elders, William (2013). Josquin des Pres and His Musical Legacy: An Introductory Guide. Leuven University Press: Leuven. ISBN978-90-5867-941-3.

- Fallows, David (April 1996). "Josquin and Milan". Plainsong & Medieval Music. five (1): 69–80. doi:10.1017/S0961137100001078.

- Fallows, David (2009). Josquin (1st ed.). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN978-2-503-53065-ix.

- Fallows, David (2020). Josquin (2nd ed.). Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN978-2-503-56674-0.

- Fallows, David (26 November 2021). "Josquin at 500". Early Music. caab065. doi:10.1093/em/caab065.

- Godt, Irving (Fall 1977). "Motivic Integration in Josquin's "Motets"". Journal of Music Theory. 21 (2): 264–292. doi:10.2307/843491. JSTOR 843491.

- Higgins, Paula (Fall 2004). "The Apotheosis of Josquin des Prez and Other Mythologies of Musical Genius". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 57 (3): 443–510. doi:ten.1525/jams.2004.57.3.443. JSTOR x.1525/jams.2004.57.three.443.

- Kellman, Herbert (2009). "Dad and Granddad Were Cops: Josquin's Ancestry". In Bloxam, 1000. Jennifer; Filocamo, Gioia; Holford-Strevens, Leofranc (eds.). Uno gentile et subtile ingenio Studies in Renaissance Music in Honor of Bonnie J. Blackburn. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. pp. 183–200. ISBN978-2-503-53163-ii.

- Lowinsky, Edward (1976). Josquin des Prez. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Macey, Patrick (1998). Bonfire Songs: Savonarola'southward Musical Legacy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN0-19-816669-9.

- Macey, Patrick; Noble, Jeremy; Dean, Jeffrey; Reese, Gustave (2011) [2001]. "Josquin (Lebloitte dit) des Prez". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:x.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.14497. ISBN978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Matthews, Lora; Merkley, Paul (Autumn 1994). "Josquin Desprez and His Milanese Patrons". The Journal of Musicology. 12 (4): 434–463. doi:10.2307/763971. JSTOR 763971.

- Matthews, Lora; Merkley, Paul (Spring 1998). "Iudochus de Picardia and Jossequin Lebloitte dit Desprez: The Names of the Singer(due south)". The Periodical of Musicology. sixteen (2): 200–226. doi:10.2307/764140. JSTOR 764140.

- Merkley, Paul (Fall 2001). "Josquin Desprez in Ferrara". The Periodical of Musicology. 18 (4): 544–583. doi:10.1525/jm.2001.18.four.544. JSTOR 10.1525/jm.2001.18.4.544.

- Noble, Jeremy. "Josquin Desprez (works)" The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. London, Macmillan, 1980. (xx vol.) ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Pietschmann, Klaus (2021). "Ein Graffito von Josquin Desprez auf der Cantoria der Sixtinischen Kapelle". Die Musikforschung (in German). 52 (two): 204–207. doi:10.52412/mf.1999.H2.887. JSTOR 41123290. S2CID 140790222.

- Roth, Adalbert (2000). "Judocus de Kessalia and Judocus de Pratis". Recercare. 12: 23–51. JSTOR 41701332.

- Reese, Gustave (1954). Music in the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN0-393-09530-4.

- Reese, Gustave. "Josquin Desprez (biography)" The New Grove Lexicon of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. London, Macmillan, 1980. (xx vol.) ISBN 1-56159-174-two.

- Reese, Gustave; Noble, Jeremy; Lockwood, Lewis; Owens, Jessie Ann; Haar, James; Kerman, Joseph; Stevenson, Robert (1984) [1980]. The New Grove High Renaissance Masters: Josquin, Palestrina, Lassus, Byrd, Victoria. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians: The Composer Biography Series. London: Macmillan. ISBN0-393-30093-v.

- Sherr, Richard, ed. (2000). The Josquin Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-816335-0.

- Blackburn, Bonnie J. (2000). "Masses Based on Pop Songs and Solmization Syllables". In Sherr, Richard (ed.). The Josquin Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford Academy Press. pp. 51–88. ISBN978-0-19-816335-0.

- Milsom, John (2000). "Motets for 5 or More Voices". In Sherr, Richard (ed.). The Josquin Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-816335-0.

- Planchart, Alejandro (2000). "Masses on Plainsong Cantus Firmi". In Sherr, Richard (ed.). The Josquin Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Printing. pp. 89–150. ISBN978-0-19-816335-0.

- Litterick, Louise (2000). "Chansons for Iii and Iv Voices". In Sherr, Richard (ed.). The Josquin Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 335–392. ISBN978-0-19-816335-0.

- Wegman, Rob C. (2000). "Who Was Josquin?". In Sherr, Richard (ed.). The Josquin Companion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 21–50. ISBN978-0-19-816335-0.

- Sherr, Richard (27 April 2017). "Josquin des Prez". Oxford Bibliographies: Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199757824-0194. (subscription required)

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century. The Oxford History of Western Music. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-538481-nine.

- Woolfe, Zachary (29 April 2021). "The Renaissance's Most Influential Composer, 500 Years Subsequently – Centuries after his death, Josquin des Prez's achievements every bit a musical "magician-mathematician" remain stunning". The New York Times . Retrieved 29 Apr 2021.

Farther reading [edit]

Meet and Fallows (2020, pp. 469–495) and Sherr (2017) for an extensive bibliography

- Charles, Sydney R. Josquin des Prez: A Guide to Enquiry. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1983.

- Clutterham, Leslie. "Dating Josquin's Enigmatic Motet Illibata Dei virgo nutrix". Choral Journal 38, no. 3 (October 1997): ix–14. Online version every bit "Auobiographical [sic] Constructions in Josquin's Motet Illibata Dei virgo nutrix: Evidence for a Later Dating" (Accessed viii May 2012).

- Duffin, Ross W., ed. A Josquin Anthology. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-353218-2.

- Elders, Willem, ed. New Josquin Edition, thirty vols. Utrecht: Koninklijke Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 1987– . ISBN 978-90-6375-051-0.

- Elders, Willem, and Frits de Haen, eds. Proceedings of the International Josquin Symposium, Utrecht 1986 . Utrecht: Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis, 1986. ISBN 90-6375-148-vi.

- Fiore, Carlo. Josquin des Prez. L'Epos: Palermo, 2003, ISBN 978-88-8302-220-three.

- Gleason, Harold, and Warren Becker. Music in the Eye Ages and the Renaissance. Bloomington, Indiana: Frangipani Press, 1981. ISBN 0-89917-034-Ten.

- Steib, Murray. "A Study in Fashion, or Josquin or Non Josquin: The Missa Allez regretz Question". The Journal of Musicology 16, 4 (Autumn, 1998): 519–544.

External links [edit]

- Josquin Research Project, a big-scale database of Josquin'due south work

- Biography and discography from The Medieval Music & Arts Foundation

- List of compositions by Despres, Josquin at the Digital Prototype Archive of Medieval Music

- Free scores by Josquin des Prez in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Gratis scores past Josquin des Prez at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- The Mutopia Project has compositions past Josquin des Prez

- Listen to free recordings of compositions from the Umeå Academic Choir

longoriawrour1951.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josquin_des_Prez

0 Response to "in what way is the composer josquin related to palestrina and the catholic church?"

Post a Comment